1.6 Events and how to handle them

Event handling

As you already know, events are the fuel which propel the application’s movements. All events come to the event manager, which is responsible for dispatching them to all the application components. This also means that some of the events may launch some of your callbacks, which makes you responsible for preparing the proper reactions to the user’s actions.

Now it’s time to show you some details of the events’ lives and anatomy. We’ll also show you how the events are able to influence a widget’s state, and how you control the event manager’s behavior.

For now, however, we want you to focus your attention on a very helpful method we’ll use to arrange communication between you and your application.

Of course, you can use the regular print() function to show messages and present a debug trace. The output will appear in the standard Python console, without affecting the application window. It’s okay if used in the early stages of development, but it’s very inelegant if you want the application to behave in a mature way.

The function we’ll use for our experiments is named showinfo(), it comes from the messagebox module, and it needs two arguments which are strings:

- output

messagebox.showinfo(title, info)

- the first string will be used by the function to title the message box which will appear on the screen; you can use an empty string, and the box will be untitled then;

- the second string is a message to display inside the box; the string can be of any length (but remember, the screen isn’t elastic and won’t stretch if you’re going to display a whole encyclopedia volume); note: you can use the

\ndigraph to visually break the info into separate lines.

We’ll ask the showinfo() function to show us its possibilities.

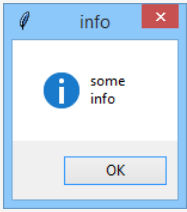

In the editor we've provided a very simple code demonstrating how showinfo() works:

import tkinter from tkinter import messagebox def clicked(): messagebox.showinfo("info", "some\ninfo") window = tkinter.Tk() button_1 = tkinter.Button(window, text="Show info", command=clicked) button_1.pack() button_2 = tkinter.Button(window, text="Quit", command=window.destroy) button_2.pack() window.mainloop()

Note the \n embedded inside the info string.

And this is what the final message box looks like:

If your widget is a clickable one, you can connect a callback to it using its command property, while the property can be initially set by the constructor invocation.

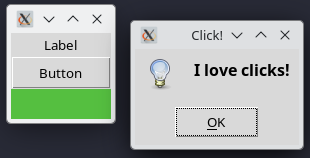

We’ve already practiced this, so the snippet in the editor won’t be a surprise to you.

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import messagebox def click(): tk.messagebox.showinfo("Click!","I love clicks!") window = tk.Tk() label = tk.Label(window, text="Label") label.pack() button = tk.Button(window, text="Button", command=click) button.pack(fill=tk.X) frame = tk.Frame(window, height=30, width=100, bg="#55BF40") frame.pack(); window.mainloop()

Note – there are three widgets in all, but only one of them (the Button) is clickable by nature. Such a widget’s constructor is equipped with the command parameter, which is used to bind a callback.

The window along with its message box looks like this:

Some of the widgets (especially those that are not clickable by nature) have neither a command property nor a constructor parameter of that name.

Fortunately, you’re still able to bind a callback to any of the events it may receive (including clicks, of course) and this is done with a method named – it couldn’t be anything else – bind():

- output

widget.bind(event, callback)

The bind() method needs two arguments:

the event you want to launch your callback with; the callback itself.

Looks clear, doesn’t it?

Of course, there are two questions that should be answered immediately:

- Q: What is an event from the event controller’s point of view?

- A: It’s an object carrying some useful info about what actually happens when the event has been induced (by the user or by another factor).

- Q: How are the events identified?

- A: By unique names – each event has its own name and the name is just a unified string.

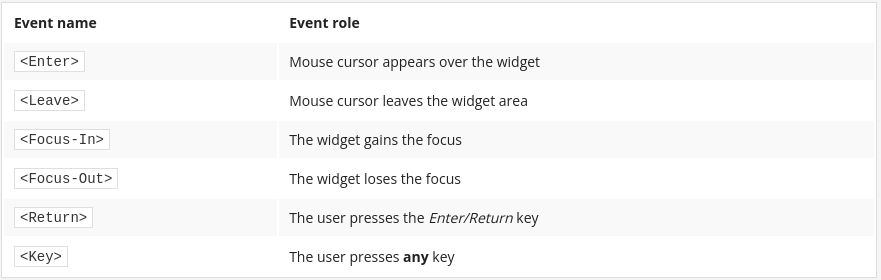

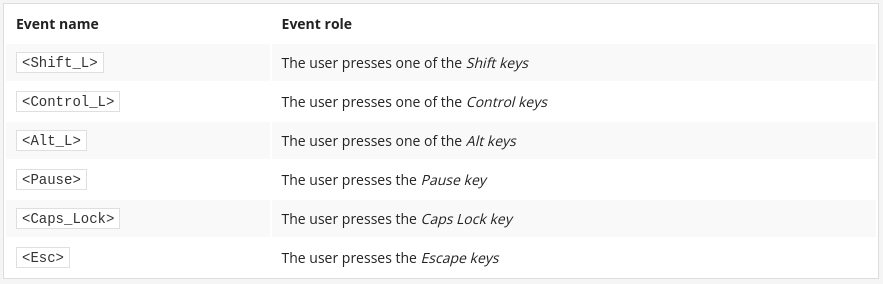

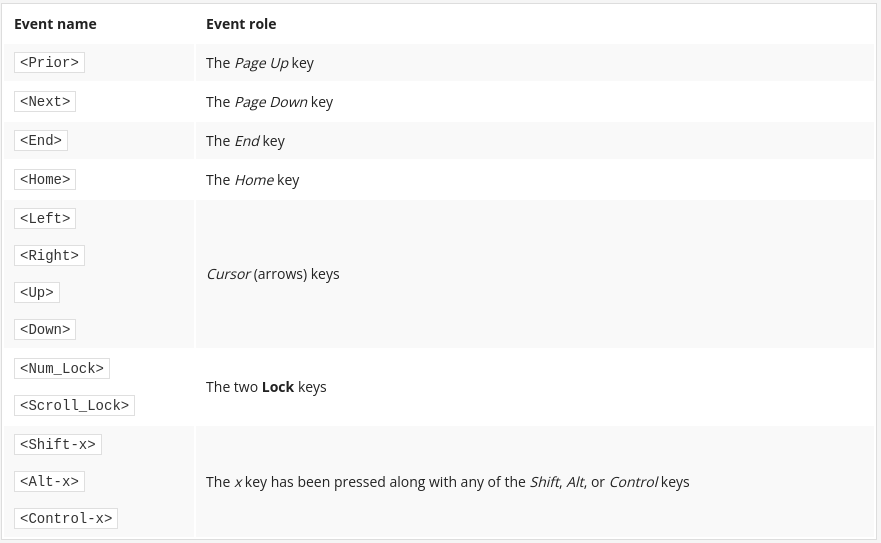

Useful events

We’ve gathered some of the most usable event names – don’t try to learn them by heart.

Don’t be afraid if some of the events look a bit suspicious. You’ll get used to them soon.

Note:

- a callback designed for usage with the command property/parameter is a parameterless function;

- a callback intended to cooperate with the

bind()method is a one-parameter function (the callback’s argument carries some info about the captured event) - fortunately, it doesn’t mean that you have to define two different callbacks for those two applications, and this is how we’ll cope with the above requirements:

def callback(ev=None): : :

- the callback will work flawlessly in both of these contexts, and moreover, it’ll give you the chance to identify which one of the two possible styles of launch has just occurred.

We’re going to change our previous example a bit by making it sensitive to more than just one click.

We've provided the newer version of our code in the editor.

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import messagebox def click(event=None): tk.messagebox.showinfo("Click!", "I love clicks!") window = tk.Tk() label = tk.Label(window, text="Label") label.bind("<Button-1>", click) # Line I label.pack() button = tk.Button(window, text="Button", command=click) button.pack(fill=tk.X) frame = tk.Frame(window, height=30, width=100, bg="#55BF40") frame.bind("<Button-1>", click) # Line II frame.pack() window.mainloop()

Pay attention to Line I and Line II in the above code. They show the way in which you can bind your callback to any of non-clickable widgets. The bind remains active to the end of the application’s work, but you can also manually unbind the event at any moment (and bind it again when you wish).

We encourage you to play with the code – test the behavior of some of the other events. It’ll be fun… we think.

We’ve said previously that an event is actually an object. Let’s shed some light on that.

An event object is an instantiation of the Event class. Actually, it’s a container filled with some more or less helpful data. The data describe all the circumstances which are accompanied within the event, and it is dispatched to a number of the object’s properties.

class Event:

:

:

Note: not all properties have meaning for every event. If the event is related to some of the mouse actions, the object’s parts referring to the keyboard remain uninitialized, and vice versa.

Let us show you some of the properties.

Let’s modify our code again. We want it to unveil some info coming in with the event object. Look at the code in the editor.

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import messagebox def click(event=None): if event is None: tk.messagebox.showinfo("Click!", "I love clicks!") else: string = "x=" + str(event.x) + ",y=" + str(event.y) + \ ",num=" + str(event.num) + ",type=" + event.type tk.messagebox.showinfo("Click!", string) window = tk.Tk() label = tk.Label(window, text="Label") label.bind("<Button-1>", click) label.pack() button = tk.Button(window, text="Button", command=click) button.pack(fill=tk.X) frame = tk.Frame(window, height=30, width=100, bg="#55BF40") frame.bind("<Button-1>", click) frame.pack() window.mainloop()

We encourage you again to carry out some experiments with this code. Use it to discover the event’s anatomy in detail.

A callback bound to a certain event may be unbound at any moment.

Let’s analyze the process in relation to clickable widgets i.e., those having the command property and using the command constructor’s parameter.

If you unbind a callback from an event, the widget stops reacting to the event. If you want to reverse this action, you must bind the callback again.

We haven’t said a word on modifying a widget’s properties, and we’re going to discuss it thoroughly in the next section, so please forgive us for only doing it briefly now.

If you want to modify a property named prop, existing within a widget named wid, and you’re going set its value to val, you can use the config() method, just like here:

wid.config(prop=val)

This means that if you want to unbind your current callback from a Button named b1, you would use an invocation like this one:

b1.config(command=lambda:None)

This binds an empty (i.e., doing absolutely nothing) function to the widget’s callback.

Let’s test it.

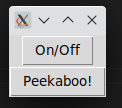

Our application creates a window with two buttons in it. The first one works as an on/off switch, while the switch changes the behavior of the second button. When the switch is ON, clicking the second button activates a message box. When the switch if OFF, clicking the second button has no effect. Moreover, the second button’s title changes according to the switch’s state.

Note the method we use to change the button’s title.

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import messagebox def on_off(): global switch if switch: button_2.config(command=lambda: None) button_2.config(text="Gee!") else: button_2.config(command=peekaboo) button_2.config(text="Peekaboo!") switch = not switch def peekaboo(): messagebox.showinfo("", "PEEKABOO!") def do_nothing(): pass switch = True window = tk.Tk() buton_1 = tk.Button(window, text="On/Off", command=on_off) buton_1.pack() button_2 = tk.Button(window, text="Peekaboo!", command=peekaboo) button_2.pack() window.mainloop()

The two faces of our window look like this:

Now we’ll do the same trick again, but this time with the non-clickable widget.

To unbind a callback previously bound with the bind() method invocation, you need to use the unbind() method:

widget.unbind(event)

The method requires one argument identifying the event being unbound.

Note: the information about a previously used callback is lost. You cannot retrieve it automatically and you must repeat the bind() invocation.

Let’s jump into the code.

import tkinter as tk def on_off(): global switch if switch: label.unbind("<Button-1>") else: label.bind("<Button-1>", rhyme) switch = not switch def rhyme(dummy): global word_no, words word_no += 1 label.config(text=words[word_no % len(words)]) switch = True words = ["Old", "McDonald", "Had", "A", "Farm"] word_no = 0 window = tk.Tk() button = tk.Button(window, text="On/Off", command=on_off) button.pack() label = tk.Label(window, text=words[0]) label.bind("<Button-1>", rhyme) label.pack() window.mainloop()

The application contains two widgets: one Button (clickable) and one Label (non-clickable).

We bind a callback to the Label, causing it to display (in a loop) the first five words of this old but good rhyme (please dive into the rhyme() function to check out how we’ve done it).

This functionality can be turned off and on by clicking the button. As you can see, the on_off() callback binds and unbinds the label’s callback.

Try to modify the code to use a few other events to trigger the switch.

The main tkinter window has a method named bind_all() which binds a callback to all currently existing widgets.

There is also a method named unbind_all() which reverts the first method’s effects.

window.bind_all(event, callback) window.unbind_all(event)

We used the bind_all() method to bind the one and the same callback to all three widgets, whether clickable or not. Look at the code we've provided in the editor.

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import messagebox def hello(dummy): messagebox.showinfo("", "Hello!") window = tk.Tk() button = tk.Button(window, text="On/Off") button.pack() label = tk.Label(window, text="Label") label.pack() frame = tk.Frame(window, bg="yellow", width=100, height=20) frame.pack() window.bind_all("<Button-1>", hello) window.mainloop()

Play with the code. Don’t worry, it’s safe.

Now we’re going to take you on a trip to Widget land. It’ll be an exciting journey, we promise.