1.4 Talking to JSON in Python

Working with the JSON module in Python

Now that we're familiar with JSON essentials, it's time to learn how to use it with Python. We're a little worried you may think that we want you to laboriously build JSON messages, fretting over all these brackets, parentheses and colons, and to break down complex JSON lines into prime factors. Nothing could be further from the truth! We’re not in the habit of coming up with such crazy ideas, although, to be honest, it's not as complex as it may seem and we're convinced that you’d be able to cope with such a challenge. Fortunately, you don't need to.

Why?

Because there’s a Python module – named JSON – which is able to perform all those drudgeries for you.

How do we start a new adventure? It's obvious, and we're sure that you knew it before we asked:

import json

The first JSON module's power is the ability to automatically convert Python data (not all of it and not always) into a JSON string. If you want to carry out such an operation, you may use a function named dumps().

Note: the ’s at the end of the function's name means string. There is a very similar function with the name deprived of this suffix which writes the JSON string to the file for file-like streams.

The function does what it promises – it takes data (even somewhat complicated data) and produces a string filled with a JSON message. Of course, dumps() isn't a prophet and it's not able to read your mind, so don't expect miracles.

Let’s start with some simple snippets.

The first of our samples takes a number and outputs a number – we don't expect anything more:

import json electron = 1.602176620898E10−19 print(json.dumps(electron))

The code outputs:

- output

16021766189.98

Note: the notation is different but the value remains the same. Check it yourself.

Let's do the same but with a string, like this:

import json comics = '"The Meaning of Life" by Monty Python\'s Flying Circus' print(json.dumps(comics))

The code outputs:

- output

"\"The Meaning of Life\" by Monty Python's Flying Circus"

As you can see, all JSON requirements have been met.

Now’s a good moment to introduce a list. What do you think about this example?

import json my_list = [1, 2.34, True, "False", None, ['a', 0]] print(json.dumps(my_list))

As you can see, there are actually two lists. Is that a problem? Not at all!

The code prints:

- output

[1, 2.34, True, "False", null, ["a", 0]]

We want to ask you a question here – what will happen if we use a tuple instead of a list? The answer is predictable – nothing. As JSON cannot distinguish between lists and tuples, both of these are converted into JSON arrays.

Let’s check a dictionary. Here’s a simple test:

import json my_dict = {'me': "Python", 'pi': 3.141592653589, 'data': (1, 2, 4, 8), 'set': None} print(json.dumps(my_dict))

And this is the output of the code:

- output

{"me": "Python", "pi": 3.141592653589, "data": [1, 2, 4, 8], "friend": "JSON", "set": null}

Now we’re ready to draw some conclusions.

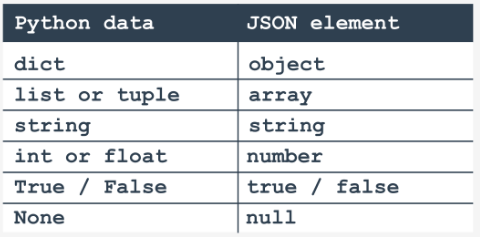

As you can see, Python uses a small set of simple rules to build JSON messages from its native data. Here it is:

It looks simple and consistent. So where’s the trap?

The trap is here:

import json class Who: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age some_man = Who('John Doe', 42) print(json.dumps(some_man))

The output you'll see is extremely disappointing:

- output

TypeError: Object of type 'Class' is not JSON serializable

Yes, that's the clue. You cannot just dump the content of an object, even an object as simple as this one.

Of course, if you don't need anything more than a set of object properties and their values, you can perform a (somewhat dirty) trick and dump not the object itself, but its __dict__ property content. It will work, but we expect more.

import json class Who: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age def encode_who(w): if isinstance(w, Who): return w.__dict__ else: raise TypeError(w.__class__.__name__ + ' is not JSON serializable') some_man = Who('John Doe', 42) print(json.dumps(some_man, default=encode_who))

The second approach is based on the fact that the serialization is actually done by the method named default(), which is a part of the json.JSONEncoder class. It gives you the opportunity to overload the method defining a JSONEncoder's subclass and to pass it into dumps() using the keyword argument named cls – just like in the code we've provided in the editor.

import json class Who: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age class MyEncoder(json.JSONEncoder): def default(self, w): if isinstance(w, Who): return w.__dict__ else: return super().default(self, z) some_man = Who('John Doe', 42) print(json.dumps(some_man, cls=MyEncoder))

As you can see, we are released from the obligation to raise any exceptions. Nice, isn't it?

The code produces the same output as the previous one:

- output

{"name": "John Doe", "age": 42}

It seems that we know enough about how to travel from Python land to JSON world, but still know anything about how to return. Let's take care of it.

The function which is able to get a JSON string and to turn it into Python data is named loads() – it takes a string (hence the s at the end of its name) and tries to create a Python entity corresponding to the received data.

This is how it goes:

import json jstr = '16021766189.98' electron = json.loads(jstr) print(type(electron)) print(electron)

The code prints:

- output

<class 'float'> 16021766189.98

The loads() function is able to cope with strings, too. Take a look at the snippet:

import json jstr = '"\\"The Meaning of Life\\" by Monty Python\'s Flying Circus"' comics = json.loads(jstr) print(type(comics)) print(comics)

Can you see the double backslashes inside the jstr? Are they really needed?

Yes, they are, as we have to deliver an exact JSON string into the loads(). This means that the backslash must precede all quotes existing within the string. Removing any of them will make the string invalid and loads() will not like it for sure.

The code outputs:

- output

<class 'str'> "The Meaning of Life" by Monty Python's Flying Circus

And what about lists? Is loads() smart enough to interpret them correctly?

Yes, it is – take a look:

import json jstr = '[1, 2.34, true, "False", null, ["a", 0]]' my_list = json.loads(jstr) print(type(my_list)) print(my_list)

The code prints:

- output

<class 'list'> [1, 2.34, True, 'False', None, ['a', 0]]

We expect that the JSON object will be processed correctly.

Yes, it will:

import json json_str = '{"me":"Python","pi":3.141592653589, "data":[1,2,4,8],"friend":"JSON","set": null}' my_dict = json.loads(json_str) print(type(my_dict)) print(my_dict)

The code prints:

- output

<class 'dict'> {'me': 'Python', 'pi': 3.141592653589, 'data': [1, 2, 4, 8], 'friend': 'JSON', 'set': None}

Our tests show that the table we presented before works successfully in both directions. There’s only one specific difference: if a number encoded inside a JSON string doesn't have any fraction part, Python will create an integer number, or a float number otherwise.

But what about Python's objects – can we deserialize them in the same way as we performed the serialization?

As you probably expect, deserializing an object may require some additional steps. Yes, indeed. As loads() isn't able to guess what object (of which class) you actually need to deserialize, you have to provide this information.

Take a look at the snippet we've provided in the editor window.

import json class Who: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age def encode_who(w): if isinstance(w, Who): return w.__dict__ else: raise TypeError(w.__class__.__name__ + 'is not JSON serializable') def decode_who(w): return Who(w['name'], w['age']) old_man = Who("Jane Doe", 23) json_str = json.dumps(old_man, default=encode_who) new_man = json.loads(json_str, object_hook=decode_who) print(type(new_man)) print(new_man.__dict__)

As you can see, there’s a keyword argument name object_hook, which is used to point to the function responsible for creating a brand new object of a needed class and for filling it with actual data.

Note: the decode_who() function receives a Python entity, or more specifically – a dictionary. As Who's constructor expects two ordinary values, a string and a number, not a dictionary, we have to use a little trick – we've employed the double * operator to turn the dictionary into a list of keyword arguments built out of the dictionary's key:value pairs. Of course, the keys in the dictionary must have the same names as the constructor's parameters.

Note: the function, specified by the object_hook will be invoked only when the JSON string describes a JSON object. Sorry, there are no exceptions to this rule.

As previously, a purer object approach is also possible, and is based on redefining the JSONDecoder class. Unfortunately, this variant is more complicated than its encoding counterpart.

We don't need to rewrite any method, but we do have to redefine the superclass constructor, which makes our job a little more painstaking. The new constructor is intended to do just one trick – set a function for object creation.

As you can see, this is exactly the same thing we did before, but expressed at a different level.

import json class Who: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age class MyEncoder(json.JSONEncoder): def default(self, w): if isinstance(w, Who): return w.__dict__ else: return super().default(self, z) class MyDecoder(json.JSONDecoder): def __init__(self): json.JSONDecoder.__init__(self, object_hook=self.decode_who) def decode_who(self, d): return Who(**d) some_man = Who('Jane Doe', 23) json_str = json.dumps(some_man, cls=MyEncoder) new_man = json.loads(json_str, cls=MyDecoder) print(type(new_man)) print(new_man.__dict__)

We're glad to inform you that we’ve now gathered enough knowledge to move on to the next level. We’re going to return to some network issues, but we also want to show you some handy new tools.